Le 15 avril 2019, le Conseil de l’UE adoptait, en co-décision avec le Parlement européen, la directive sur le droit d’auteur dans le marché unique numérique (qui doit encore être publiée au Journal Officiel). Le communiqué de presse du Conseil de l’UE du 15 avril 2019 (à comparer avec celui de la Commission) indique sobrement que: “L’UE adapte les règles relatives au droit d’auteur à l’ère numérique”. Depuis le milieu des années 1990, le droit d’auteur doit s’adapter à l’environnement numérique. Rien de nouveau donc?

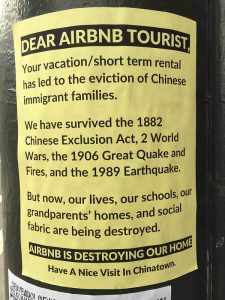

La question de savoir si le droit d’auteur est “fit” pour le monde numérique revient régulièrement dans l’actualité législative et aussi judiciaire. Le précédent bloc législatif, la directive 2001/29 sur le droit d’auteur dans la société de l’information, visait aussi à ajuster ce droit. L’équilibre à trouver entre les parties prenantes évolue avec les technologies, les applications et les marchés: au début de l’Internet, pas de YouTube ou Facebook, pas de connexion rapide, ni d’écrans multiples. Les récents modes de diffusion et de consommation requièrent de nouveaux équilibres entre les usagers, mieux servis en contenus et plus exigeants en termes d’accès, les créateurs, qui peinent à se faire rémunérer pour les usages démultipliés de leurs oeuvres, et les nouveaux intermédiaires que sont les plateformes de contenus.

Le législateur européen a-t-il trouvé le point d’équilibre entre la “freedom” souhaitée par les internautes et la “fairness” pour les créateurs et producteurs. “Free & fair” (voir la vidéo associée au communiqué de presse du Conseil) est décidément un slogan à la mode: cette formule magique est aussi invoquée pour la nouvelle génération d’accords commerciaux. Mais reste un point difficile à atteindre.

L’une des questions à vérifier est de savoir si l’article 17 relatif à “l’utilisation de contenus protégés par des fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne” est ce “texte équilibré” vanté par le Conseil. En tout cas, il n’est pas court:

Article 17. Utilisation de contenus protégés par des fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne

1. Les États membres prévoient qu’un fournisseur de services de partage de contenus en ligne effectue un acte de communication au public ou un acte de mise à la disposition du public aux fins de la présente directive lorsqu’il donne au public l’accès à des œuvres protégées par le droit d’auteur ou à d’autres objets protégés qui ont été téléversés par ses utilisateurs. Un fournisseur de services de partage de contenus en ligne doit dès lors obtenir une autorisation des titulaires de droits visés à l’article 3, paragraphes 1 et 2 de la directive 2001/29/CE, par exemple en concluant un accord de licence, afin de communiquer au public ou de mettre à la disposition du public des œuvres ou d’autres objets protégés.

2. Les États membres prévoient que, lorsqu’un fournisseur de services de partage de contenus en ligne obtient une autorisation, par exemple en concluant un accord de licence, cette autorisation couvre également les actes accomplis par les utilisateurs des services relevant du champ d’application de l’article 3 de la directive 2001/29/CE lorsqu’ils n’agissent pas à des fins commerciales ou lorsque leur activité ne génère pas de revenus significatifs.

3. Quand un fournisseur de services de partage de contenus en ligne procède à un acte de communication au public ou à un acte de mise à la disposition du public, dans les conditions fixées par la présente directive, la limitation de responsabilité établie à l’article 14, paragraphe 1, de la directive 2000/31/CE ne s’applique pas aux situations couvertes par le présent article.

Le premier alinéa du présent paragraphe n’affecte pas l’éventuelle application de l’article 14, paragraphe 1, de la directive 2000/31/CE à ces fournisseurs de services pour des finalités ne relevant pas du champ d’application de la présente directive.4. Si aucune autorisation n’est accordée, les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne sont responsables des actes non autorisés de communication au public, y compris la mise à la disposition du public, d’œuvres protégées par le droit d’auteur et d’autres objets protégés, à moins qu’ils ne démontrent que:

a) ils ont fourni leurs meilleurs efforts pour obtenir une autorisation; et

b) ils ont fourni leurs meilleurs efforts, conformément aux normes élevées du secteur en matière de diligence professionnelle, pour garantir l’indisponibilité d’œuvres et d’autres objets protégés spécifiques pour lesquels les titulaires de droits ont fourni aux fournisseurs de services les informations pertinentes et nécessaires; et en tout état de cause

c) ils ont agi promptement, dès réception d’une notification suffisamment motivée de la part des titulaires de droits, pour bloquer l’accès aux œuvres et autres objets protégés faisant l’objet de la notification ou pour les retirer de leurs sites internet, et ont fourni leurs meilleurs efforts pour empêcher qu’ils soient téléversés dans le futur, conformément au point b).5. Pour déterminer si le fournisseur de services a respecté les obligations qui lui incombent en vertu du paragraphe 4, et à la lumière du principe de proportionnalité, les éléments suivants sont, entre autres, pris en considération:

a) le type, l’audience et la taille du service, ainsi que le type d’œuvres ou d’autres objets

protégés téléversés par les utilisateurs du service; et

b) la disponibilité de moyens adaptés et efficaces et leur coût pour les fournisseurs de services.6. Les États membres prévoient que, à l’égard de nouveaux fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne dont les services ont été mis à la disposition du public dans l’Union depuis moins de trois ans et qui ont un chiffre d’affaires annuel inférieur à 10 millions d’euros calculés conformément à la recommandation 2003/361/CE de la Commission, les conditions au titre du régime de responsabilité énoncé au paragraphe 4 sont limitées au respect du paragraphe 4, point a), et au fait d’agir promptement, lorsqu’ils reçoivent une notification suffisamment motivée, pour bloquer l’accès aux œuvres ou autre objets protégés faisant l’objet de la notification ou pour les retirer de leurs site internet.

Lorsque le nombre moyen de visiteurs uniques par mois de tels fournisseurs de services dépasse les 5 millions, calculé sur la base de l’année civile précédente, ils sont également tenus de démontrer qu’ils ont fourni leurs meilleurs efforts pour éviter d’autres téléversements des œuvres et autres objets protégés faisant l’objet de la notification pour lesquels les titulaires de droits ont fourni les informations pertinentes et nécessaires.

7. La coopération entre les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne et les titulaires de droits ne conduit pas à empêcher la mise à disposition d’œuvres ou d’autres objets protégés téléversés par des utilisateurs, qui ne portent pas atteinte au droit d’auteur et aux droits voisins, y compris lorsque ces œuvres ou autres objets protégés sont couverts par une exception ou une limitation.

Les États membres veillent à ce que les utilisateurs dans chaque État membre puissent se prévaloir de l’une quelconque des exceptions ou limitations existantes suivantes lors du téléversement et de la mise à dispostion de contenus générés par les utilisateurs sur les services de partage de contenus en ligne:

a) citation, critique, revue;

b) utilisation à des fins de caricature, de parodie ou de pastiche.8. L’application du présent article ne donne lieu à aucune obligation générale de surveillance.

Les États membres prévoient que les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne fournissent aux titulaires de droits, à leur demande, des informations adéquates sur le fonctionnement de leurs pratiques en ce qui concerne la coopération visée au paragraphe 4 et, en cas d’accords de licence conclus entre les fournisseurs de services et les titulaires de droits, des informations sur l’utilisation des contenus couverts par les accords.

9. Les États membres prévoient la mise en place par les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne d’un dispositif de traitement des plaintes et de recours rapide et efficace, à la disposition des utilisateurs de leurs services en cas de litige portant sur le blocage de l’accès à des œuvres ou autres objets protégés qu’ils ont téléversés ou sur leur retrait.

Lorsque des titulaires de droits demandent à ce que l’accès à leurs œuvres ou autres objets protégés spécifiques soit bloqué ou à ce que ces œuvres ou autres objets protégés soient retirés, ils justifient dûment leurs demandes. Les plaintes déposées dans le cadre du dispositif prévu au premier alinéa sont traitées sans retard indu et les décisions de blocage d’accès aux contenus téléversés ou de retrait de ces contenus font l’objet d’un contrôle par une personne physique. Les États membres veillent à ce que des mécanismes de recours extrajudiciaires soient disponibles pour le règlement des litiges. Ces mécanismes permettent un règlement impartial des litiges et ne privent pas l’utilisateur de la protection juridique accordée par le droit national, sans préjudice du droit des utilisateurs de recourir à des voies de recours judiciaires efficaces. En particulier, les États membres veillent à ce que les utilisateurs puissent s’adresser à un tribunal ou à une autre autorité judiciaire compétente pour faire valoir le bénéfice d’une exception ou d’une limitation au droit d’auteur et aux droits voisins.

La présente directive n’affecte en aucune façon les utilisations légitimes, telles que les utilisations relevant des exceptions ou limitations prévues par le droit de l’Union, et n’entraîne aucune identification d’utilisateurs individuels ni de traitement de données à caractère personnel, excepté conformément à la directive 2002/58/CE et au règlement (UE)2016/679.

Les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne informent leurs utilisateurs, dans leurs conditions générales d’utilisation, qu’ils peuvent utiliser des œuvres et autres objets protégés dans le cadre des exceptions ou des limitations au droit d’auteur et aux droits voisins prévues par le droit de l’Union.

10. À compter du … [date d’entrée en vigueur de la présente directive], la Commission organise, en coopération avec les États membres, des dialogues entre parties intéressées afin d’examiner les meilleures pratiques pour la coopération entre les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne et les titulaires de droits. Après consultation des fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne, des titulaires de droits, des organisations d’utilisateurs et des autres parties prenantes concernées, et compte tenu des

résultats des dialogues entre parties intéressées, la Commission émet des orientations sur l’application du présent article, en particulier en ce qui concerne la coopération visée au paragraphe 4. Lors de l’examen des meilleures pratiques, une attention particulière doit être accordée, entre autres, à la nécessité de maintenir un équilibre entre les droits fondamentaux et le recours aux exceptions et aux limitations. Aux fins des dialogues avec les parties intéressées, les organisations d’utilisateurs ont accès aux informations adéquates fournies par les fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne sur le fonctionnement de leurs pratiques en ce qui concerne le paragraphe 4.

Pour comprendre le dédale de ce texte et imaginer comment il pourra être mis en oeuvre, il faut se poser une série de questions:

- quels sont exactement les “fournisseurs de services de partage de contenus en ligne” visés? Car il y a plateforme et plateforme – la notion qui est passée dans le langage courant n’est du reste pas juridique. Ici il s’agit de plateformes de contenus partagés par les usagers.

- quand y a-t-il responsabilité directe de ces fournisseurs pour les contenus partagés?

- que faire pour éviter d’être tenu responsable?

- quels sont les actes des usagers qui sont spécifiquement et plus clairement autorisés par l’effet de l’article 17?

- quelles sont les conditions cumulatives pour l’exonération de responsabilité de ces fournisseurs?

- quelles sont les autres obligations pesant sur ces fournisseurs?

Au-delà de ces questions qui nécessitent une analyse du texte, il faudra plus généralement se demander:

- si l’article 17 répond à ce qu’on a appelé le “value gap” (voir aussi ici)?

- si l’article 17 écarte intégralement le régime exonératoire des intermédiaires en ligne défini aux articles 12 et suivants de la directive 2000/31 sur le commerce électronique?

- si l’article 17 peut être considéré comme dangereux pour la liberté d’expression, ce qui nécessite de comparer l’équilibre trouvé avec celui qui s’était établi à partir des anciens textes applicables, dont la directive 2001/29 et la directive 2000/31 ?

- si les campagnes de lobbying menées par les ayants droit, d’un côté, et les plateformes, de l’autre, ont gonflé certains aspects du débat au point de l’obscurcir (avec exemples à l’appui)?

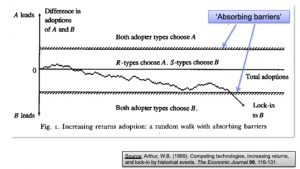

- si un régime de responsabilité avec seuil, tel que celui prévu par l’article 17 pour les plateformes d’une certaine taille, se retrouve dans d’autres législations européennes relatives aux plateformes?

- comment s’assurer qu’un texte juridique puisse rééquilibrer le rapport de force sur le terrain?

Voilà quelques questions ouvertes qui nécessitent une recherche dans les textes et dans les têtes.

A la recherche d’un équilibre.